-

Land Ownership

Part I – Feudalism, Manorialism, and Succession.

Feudalism and manorialism are a good place to start when discussing land ownership in the United Kingdom. These are related but different concepts. In feudalism a vassal is granted a fief by a lord, that is, the right to governance of a piece of land. In return the vassal typically owed the promise of military service. A classic example is knight-duty during the crusades, where knights would perform military service in the context of campaigns to the Holy Land, in exchange for the lands they had been granted under fealty. There were other forms of payment too; clergymen would offer frankalmoign; prayers for their overlord in exchange for their tenure.

Photo by Maria Pop on Pexels.com The obligations went the other way too; grantors of fiefs owed the occupants of the land a measure of protection from outside forces. Great lands were granted to the highest ranking lords by the Monarch, who was regarded as being ordained by God. From the most powerful lords there was then a chain of infeudations right down to those who effectively subsisted through their labour upon small plots of land, typically in a manorial setting:

Manorialism refers to the self- sufficient social and spatial arrangement of an economy around a medieval manor. This is said to have originated in Roman Times and was driven by agricultural activity with the labourers (originally) paying the lord in-kind with their labour. As the economy became more complex, payment was made with money instead. Manorialism as the principal form of economic contract was gradually replaced by the market economy, where the grower of produce could sell to the highest bidder, be they their lord of the manor or somebody from somewhere else who offered a better price. The promise of military service slowly began to come with the option of socage; that is, a monetary payment in lieu of knight service.

Photo by Kristina Paukshtite on Pexels.com One thing that hastened the demise of feudal systems was a law passed in 1290 known as Quia Emptores. Before Quia Emptores subinfeudation was commonplace. If a nobleman had been granted a fief he could then take part of it and subinfeudate to another individual, who then became his vassal. It was common practice for the eldest son to subinfeudate out to his younger brothers. After Quia Emptores this was forbidden and instead the tenant could only install somebody else on the land by substitution. In substitution the bond between the land and the first owner are severed, and a new bond of fealty is created between the incoming tenant, the land and the lord who forms the next link up the chain. Indeed at the time of Quia Emptores the traditions of feudalism were already undergoing disruption; many were starting to alienate themselves from their feudal land rights in exchange for monetary compensation.

There is considerable uncertainty about the development of feudal systems and what preceded them. There is some material recorded in the Venerable Bede’s 731 AD Historia Abbatum that suggests the oldest son may have been given preferential treatment in succession. There are legal stipulations from the Ninth Century that seem somewhat bizarre to us now: King Alfred of the Saxons r. AD 871-886 decreed that across the land neither an ‘abducted nun’ or any child she might bear were to receive any inheritance. The custom tending towards male-preference primogeniture recorded by the Venerable Bede may have been tightly localised. Indeed other sources such as Domesday (AD 1086) show that land could be passed from a father to his sons, the custom being perhaps to pass property over before death, this allowing for more flexible arrangements with less dispute than posthumous division. It is clear from Domesday that where there were no sons, land could also be divided, perhaps equally, among daughters. So Anglo-Saxon inheritance practices had a certain ‘elasticity’ to them1.

Around the same time that William the Conqueror conquered England primogeniture was gaining traction in Europe. It is difficult to find resources chronicling whether the practice was explicitly introduced by William among his newly installed lords but it is said that the main intentions were to prevent fragmentation of fiefs and keep a few powerful and loyal lords, rather than land ownership fracturing and the Monarch’s control becoming diluted. It is indeed difficult to unpick how the change to primogeniture took place. Henry Maine 1822-1888; comparative jurist and historian, on the topic of the origins of primogeniture:

“There are always certain ideas existing antecedently on which the sense of convenience works, and of which it can do no more than form some new combination; and to find these ideas in the present case is exactly the problem.”

Sir Matthew Hale 1609-1676, in his History of the Common Laws of England, sets out the law as he can figure it existed around the reigns of Henry I. r. 1100-1135 . and Henry II. r. 1154-1189. His exposition is based mainly off an author Glanville d. 1190, who was Chief Justicar of England during the reign of Henry II.:

‘By this law it seems to appear;

1. The eldest Son, tho’ he had Jus primogeniture, the principal Fee of his Father’s Land yet he had not all the Land.

2. That for want of Children, the Father or Mother inherited before the Brother or Sister.

3. That for want of Children, and Father, Mother, Brother and Sister, the Land defended to the Uncles and Aunts to the fifth Generation.

4. That in Successions Collateral, Proximity of Blood was preferred.

5. That the Male was preferred before the Female, i.e. The Father’s Line was preferred before the Mother’s, unless the Land descended from the Mother, and then the Mother’s Line was preferred.’

Bastards could not inherit. Provisions are also made in case of leprosy, assessed appropriately by the church, property to be transferred from brother to sister. He goes on to express his entertainment:

‘Secondly, There was another Curiosity in Law, and it was wonderful to see how much and how long it prevailed; for we find it in Use in Glanville, who wrote … Nemo potest esse Tenens & Dominus, & Homagium repellit Perquifitum: And therefore if there had been three Brothers, and the eldest Brother had enfeoffed the second, reserving Homage, and had received Homage, and then the second had died without Issue, the Land should have descended to the youngest Brother and not to the eldest Brother… as ’tis here said, for he could not pay Homage to himself’

That is, if there were three brothers, and the second paid homage to the first in a subinfeudation, then in the event the second son expired, his rights would pass to the third son and not back to the first, the reasoning being that the first son could not pay homage to himself, that is, he could not be the owner of title that required him to be his own vassal. The latin reads ‘No-one can at the same time be tenant and lord.’

Around half of what is written in Hale’s account mirrors the probate arrangements we have today. The protection for widows, who receive one third of the goods of the deceased (aka one third of the moveable estate) are just one example of how the 11th Century doctrine shares remarkable similarity to the modern day system.

References:

1. Mumby J. Anglo-Saxon inheritance. https://earlyenglishlaws.ac.uk/reference/essays/anglo-saxon-inheritance/#:~:text=Customary%20rules%20are%20thought%20to,group%20of%20closely%2Drelated%20persons. Updated n.d.

Land Ownership – Part II – Ownership Design

Primogeniture is said to have started in Normandy, it then spread to England with the invasion of William the Conqueror.

Feudalism grew organically out of manorialism, manorialism being a solution to the problem of providing food and security for subsistence farmers. The introduction of primogeniture in England may have been more deliberate however: we say that is was an ‘ownership design.’ Primogeniture had certain advantages for those who ruled using the feudal system. It prevented the fragmentation of land holdings, therefore keeping a small number of lords who could be monitored and whose allegiance could be encouraged. There was also the opportunity to claim a kind of tax: feudal relief. When William had conquered England he started from the assumption that all the land was his, and he was free to grant fiefs to whoever he wished. When one of his barons died, their eldest son had to pay money to the crown as feudal relief to allow them to take on their father’s fief. In effect, by default lands reverted to William on the deaths of his barons. By the time William was finished with his changes, the subdivision of his new baronial system in terms of fiefs granted was actually very similar to the subdivision between the Earls that had previously existed in the Anglo-Saxon system. A key difference was that the noblemen William installed were mostly Normans, not Anglo-Saxons. William the Conqueror’s management of England is a significant example of design of an ownership form using ownership design control to the ruler’s advantage.

Photo by Lisa on Pexels.com In their book ‘Mine’ two lawyers Heller and Salzman introduce ideas of ownership design and give a variety of examples, many of the best come from American History. They explore how ownership in general is governed by a short list of possible narratives2.

One of the first narratives is attachment. By this we mean that an object is owned because it is attached to another object. A typical example is that the air above and depths below land could be owned by the owner of the land, although in practice this is rarely true. Indeed one of the reasons Iraq claimed for their invasion of Kuwait in 1990 and the start of the First Gulf War was that Kuwait was accused of ‘slant-drilling’ under Iraq’s Rumaila Oil Field, that is the Kuwaiti’s are said to have been drilling diagonally or even horizontally under the Iraqi border, stealing oil that belonged to Iraq by attachment.

A second narrative is first come first served; that is, whoever got there first owns it. A good example of this is the Oklahoma Land Rush of 1889 , where at noon on 22. April 1889 settlers were allowed to cross into the ‘Unassigned Lands’ in a race to stake their claim to 160 acres under the Homestead Act of 1862.

Photo by Jeanetta Richardson-Anhalt on Pexels.com But they were not there first, the Indians had been there first, who were often forced to relocate. The key here is the idea of labour. Under the Homestead Act, he who wished to be given title of the land he claimed had to build a homestead and improve the plot through their labour for at least five years. America’s ownership form for the agricultural steading was thus designed based partly on the idea of productive labour, which the Indians’ activities did not satisfy. Ownership favouring the immigrant over the Indian was also backed up on basis of might is right, another narrative used consistently throughout history to provide a basis for ownership.

The way in which the Indians were displaced need not be looked on as universally glib however. European settlers were subsistence farmers and the idea of a homestead surrounded by heartily worked agricultural land will have had a sanctity that an apartment dwelling millennial cannot imagine. As with the reign of monarchs during feudal time, the ownership design was ordained by God, after all; Genesis 9:7 :‘Be fruitful and multiply.’’

The idea that land can be claimed by labour upon it emerged under the premise that agricultural land that sat idle should be put to use to feed the populus. Under the principle of adverse possession, where A owns land and B uses it for a time without A’s re-occupation, then B shall become the owner of the said land. This law transformed over the centuries into its modern form, where the labour aspect is less noticeable, and factors like actual possession with exclusion and intention to possess as well as land registration status contribute to the outcome of cases. At the present time in English Law, the time limitation for which the claimant must occupy is ten years. Increasingly the conditions for adverse possession become more stringent, with land registration helping to block all but the most exceptional of claims.

A key narrative which is an alternative to the attachment (or ‘under’ and ‘above’ argument) is that of capture. This doctrine most likely originates from the hunting of animals and gathering of foodstuffs, and is a kind of blend of first come first served and ownership through labour arguments. The historical application no doubt applied to animals hunted and captured on lands that lacked a clear owner, like those in the New World. We see its application more recently in oil, gas and groundwater.

Mitchell, J in Westmoreland & Cambria Nat. Gas Co. v. De Witt [1889] 18 A. 724,130 Pa.St. 235:

‘Water and oil, and still more strongly gas, may be classed by themselves, if the analogy be not too fanciful, as minerals ferae naturae [wild animals]. In common with animals, and unlike other minerals, they have the power and the tendency to escape, without the volition of the owner. Their “fugitive and wandering existence within the limits of a particular tract is uncertain”.… They belong to the owner of the land, and are part of it, so long as they are on or in it, and are subject to his control; but when they escape, and go into other land, or come under another’s control, the title of the former owner is gone. Possession of the land, therefore, is not necessarily possession of the gas. If an adjoining, or even a distant, owner, drills his own land, and taps your gas, so that it comes into his well and under his control, it is no longer yours, but his.’

So because the substance is fugacious1, in that its flow cannot be controlled and its distribution cannot (or could not) be determined, it belongs like a wild animal, to whoever can capture it through extraction2. It is important to note that the capture has to occur on the land of he who extracts, so slant drilling, as discussed above in the case of the Rumaila Oil Field, is off the menu.

A related concept to the policy of capture is that found in the case Rylands v Fletcher (1868) LR 3 HL 330. Blackburn J:

“the person who for his own purposes brings on his lands and collects and keeps there anything likely to do mischief if it escapes, must keep it in at his peril, and, if he does not do so, is prima facie answerable for all the damage which is the natural consequence of its escape”

In this case a newly constructed reservoir above a series of coal shafts flooded a neighbouring mine upon first being filled, causing significant damage. So if A has something on his land that is bound to cause mischief, and allows it to escape onto B’s land, causing damage, then A is liable for that damage.

Photo by Pixabay on Pexels.com The result of the law of capture in the Pennsylvania oil rush was a sea of ‘nodding donkeys’.2 The problem was that when there are too many wells the oil pressure drops, and the approach of sinking as many wells as possible becomes counterproductive. There are similar problems in the present day in California’s Central Valley with water, where a ‘race to the bottom’ with ever deeper wells finding a law of diminishing returns and causing only further depletion of the water table. In some places in the Central Valley it is said that the land has sunk by as much as 28 feet due to the loss of water below. This sinking problem due to depletion of the water table is the same problem as was identified in Venice, Italy. Water is surely one of the great problems that will have to be tackled more inventively with coming climatic changes and increasing population pressure in so many parts of the world. Perhaps some form of ownership design will help to prevent excessive depletion in the years to come.

But a solution was found in the case of the Pennsylvania oil wells. A new ownership design called unitization was introduced. The idea of unitization is that extraction operations straddle more than one land holding.3 The various owners of the land are then compensated under a system that assesses the contribution of their land holding to the output.

Some comparisons can be drawn with new ownership designs for fishing rights. If overfishing occurs due to a pure capture policy, then fishing communities are drawn into a law of diminishing returns. The knee jerk reaction of authorities to depletion in places like Alaska due to overfishing was to introduce straightforward catch limits where the season for any given species ended when a specified quantity had been caught. This resulted in a dangerous race for fishermen to catch as large a share of the catch limit before the season was abruptly brought to a close. It’s this race that inspired the well known TV show Deadliest Catch where Alaskan king crab fishermen race through all hours to place their crab pots, in tense competition with other fishermen trying to do the same. These kind of catch limits did help fish stocks but created an undesirable race, making the life of the fisherman only more dangerous and exhausting than it already had been.

Photo by Oziel Gu00f3mez on Pexels.com Iceland came up with an ownership design for fishing that replaced capture without the problems of catch limits: the Individual Fishing Quota, or IFQ, otherwise known as a catch share. Fishermen were assigned quotas for different species of fish before the season even started. The quotas were initially based upon how much fish different boats had caught in previous years. There are many models for a marketplace for IFQs, sometimes they can be bought, sold, or leased, in other systems they cannot and return to the government if they are unused for re-auction. The obvious major advantage is the increased stocks providing security to the fishermen that they will catch their quota. The arrangement means that if the weather is dangerous the fishermen know that they can wait for a better day to catch their share. There are also business advantages: because the catch is so much more predictable, it is considerably easier to obtain finance with the future catch as collateral. The system was very successful in Alaska, with a significant increase in profits, and has been used in Australia, New Zealand, and other US states: A good case study of unlocking value through ownership design.

Cases:

Mitchell, J in Westmoreland & Cambria Nat. Gas Co. v. De Witt [1889] 18 A. 724,130 Pa.St. 235

Rylands v Fletcher (1868) LR 3 HL 330

Other References:

1. Low C. The rule of capture: Its current status and some issues to consider. file:///C:/Users/Len/Downloads/alr,+226-227-1-PB.pdf. Updated 2009.

2. Heller M, Salzman J. Mine: How the hidden rules of ownership control our lives . Doubleday. New York.; 2021.

3. Thomson Reuters Practical Law. Glossary: Unitisation (oil & gas) (UK). https://uk.practicallaw.thomsonreuters.com/w-018-5594?originationContext=knowHow&transitionType=KnowHowItem&contextData=(sc.Default)&firstPage=true. Updated 2022.

Part III – Exclusion, Psychology and Perpetual Trusts

In his book Alchemy: The Surprising Power of Ideas that Don’t Make Sense, Rory Sutherland puts forward the suggestion that what is going to revolutionise mankind this century is not data but psychology. He gives numerous examples of where approaches are logical, but the problems are psychological. Why do we have stripey toothpaste? Because it increases the complexity of the product, we therefore assign it a higher value. Why do we even brush our teeth? Partly because we don’t want to get cavities, but possibly moreso because we are terrified of halitosis.

Photo by Oziel Gu00f3mez on Pexels.com The barriers that the ownership designs of unitization and catch shares that we have seen in Part II have to overcome are largely psychological. Unitization clearly leads to better economies of scale in oil extraction and therefore there is an obvious motivation for the economically minded landowner to ‘team up,’ not necessarily for the common good but to increase yield on capital. The psychological barrier to the individual fishing quotas established in Iceland is more difficult. The capture narrative must be overcome, there is certainly something (perhaps masochistically) attractive about setting out to trawl the ocean for the catch, whatever the elements, and unfettered by any QUANGO standing in the way. A yet more prevailing narrative to overcome is that of pure labour. There is an instinct that says he who works harder and longer should receive a greater reward, that is, greater ownership; the introduction of quotas removes competition. So new ownership designs have to overcome already existing ownership narratives for successful adoption.

Photo by Yuri Shkoda on Pexels.com A psychological concept that can be difficult to overcome is the endowment effect. This is the principle that once something becomes ours, it becomes worth more to us than it was directly before we owned it. There are several factors at play here, one of which is loss aversion, by which we mean the reason why a Wall Street trader won’t close out on his poor position, because when he does, his loss will crystallise. Another narrative to consider is that of ‘a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush,’ a new object we are offered as a replacement to the one we own may have some defect or disadvantage which is not revealed on initial inspection. Neither loss aversion or the risks of owning something new really get to the crux of what we are talking about. I put it that we form relationships with objects. Consider a friend has a twin, and you suddenly cease to see this friend, because you conclude the other twin is just as good as they are, and you spend time with the second twin instead. This circumstance causes immediate distaste. I put it that when an object becomes ours we form a loyalty to it, in the same way that we give acquaintances we have known for longer preference over those who we have most recently met. I see no reason why this approach shouldn’t be applied to land just as much as to one’s chattels.

A good place to start when thinking about the psychology of human behaviour around land ownership is with the great thinkers of the Scottish Enlightenment; David Hume, Adam Smith. Henry Home (Lord Kames) illustrates the lack of good sense in the human condition with respect to property. From his Historical Law Tracts:

‘I shall conclude this tract with a brief reflection upon the whole. While the world was rude and illiterate, the relation of property was faint and obscure. This relation was gradually unfolded, and in its growth toward maturity accompanied the growing sagacity of mankind, till it became vigorous and authoritative, as we find it at present. Men are fond of power, especially over what they call their own; and all men conspired to make the powers of property as extensive as possible. Many centuries have passed since property was carried to its utmost length. No moderate man can desire more than to have the free disposal of his goods during his life, and to name the persons who shall enjoy them after his death. Old Rome, as well as Greece, acknowledged these powers to be inherent in property; and these powers are sufficient for all the purposes to which goods of fortune can be subservient. They fully answer the purposes of commerce; and they fully answer the purposes of benevolence.’

This certainly serves as a useful word on property. He goes on:

‘But the passions of men are not to be confined within the bounds of reason: We thirst after opulence; and are not satisfied with the full enjoyment of the goods of fortune, unless it be also in our power to give them a perpetual existence, and to preserve them for ever to ourselves and our families. This purpose, we are conscious cannot be fully accomplished; but we approach to it the nearest we can, by the aid of imagination. The man who has amassed great wealth, cannot think of quitting his hold; and yet, alas! he must die and leave the enjoyment to others. To colour a dismal prospect, he makes a deed, arresting fleeting property, securing his estate to himself, and to those who represent him in an endless succession: his estate and his heirs must forever bear his name; every thing to perpetuate his memory and his wealth. How unfit for the frail condition of mortals are such swoln conceptions? The feudal system unluckily suggested a hint for gratifying this irrational appetite. Entails in England, authorified by statute, spread every where with great rapidity, till becoming a public nuisance, they were checked and defeated by the authority of judges without a statute. It was a wonderful blindness in our legislature, to encourage entails by a statute, at a time when the public interest required a statute against those which had already been imposed upon us.’

Entails refer to a kind of deed that specifies conditions for inheritance. They were used typically to keep land together with the male line and a title, removing the discretion of the descendants to leave their property to whom they wished. It is difficult to find information on these instruments but they do have a similarity to modern day trusts, and no good analysis of land ownership lacks a comment on trust law.

The idea is genius. A deed of trust is a document that sets out that A, the settlor, gives property to B, the trustee, with the condition that B looks after the property to the benefit of C, the beneficiary. So A gets what he wants from the assets held by B, without having to own them. He (or she) can effectively pause the tape on their needs and wants, and prevent any future claims from divorcing spouses. Classic junctures for a trust to commence include before marriage, and on death. In some jurisdictions C could be A; you can create a trust with yourself as the beneficiary.

Photo by Pixabay on Pexels.com A key bone of contention has been dynasty trusts , that is trusts which continue into the future indefinitely. These provide a key advantage for the settlor in that they can support future generations with income while protecting against unscrupulous spending of the capital; the threat to a fortune of bad company or gambling might be a consideration.

The law against perpetuity of trusts; that is trusts which vest forever in to the future, has its roots in the case of the 6th Duke of Norfolk, and in a complex set of arrangements: Henry, 15th Earl of Arundel, wanted to arrange the inheritance of his assets in a particular manner:

- Initially the majority of the assets were left to his eldest son, Thomas, who was mentally incapacitated and incapable of marriage. Thomas lived in an asylum in Padua, in the then Republic of Venice.

- A second, lesser portion of assets would be left to the second son, also Henry.

- On Thomas’ death the assets of Thomas would pass to Henry, but the smaller second portion of assets Henry had initially inherited would pass to the fourth son, Charles.

This is termed a shifting executory interest.

The problem was that once Thomas in Padua, by this time the 5th Duke of Norfolk, had died, his brother Henry, 6th Duke of Norfolk didn’t want to hand over the relevant assets to the fourth son Charles, his case being that an unreasonable period of time had elapsed since the shifting interest was created. And so it went to the highest court in the land, and the House of Lords held that such an entailment, or in modern terms; trust, could not remain valid for such an extended period of time. The thinking at the time was that allowing interests that vest too far into the future tied up assets for future generations in an unhealthy way that damaged the flow of money in an economic sense. Attempts to control property beyond the grave were unattractively termed ‘the dead hand’.1

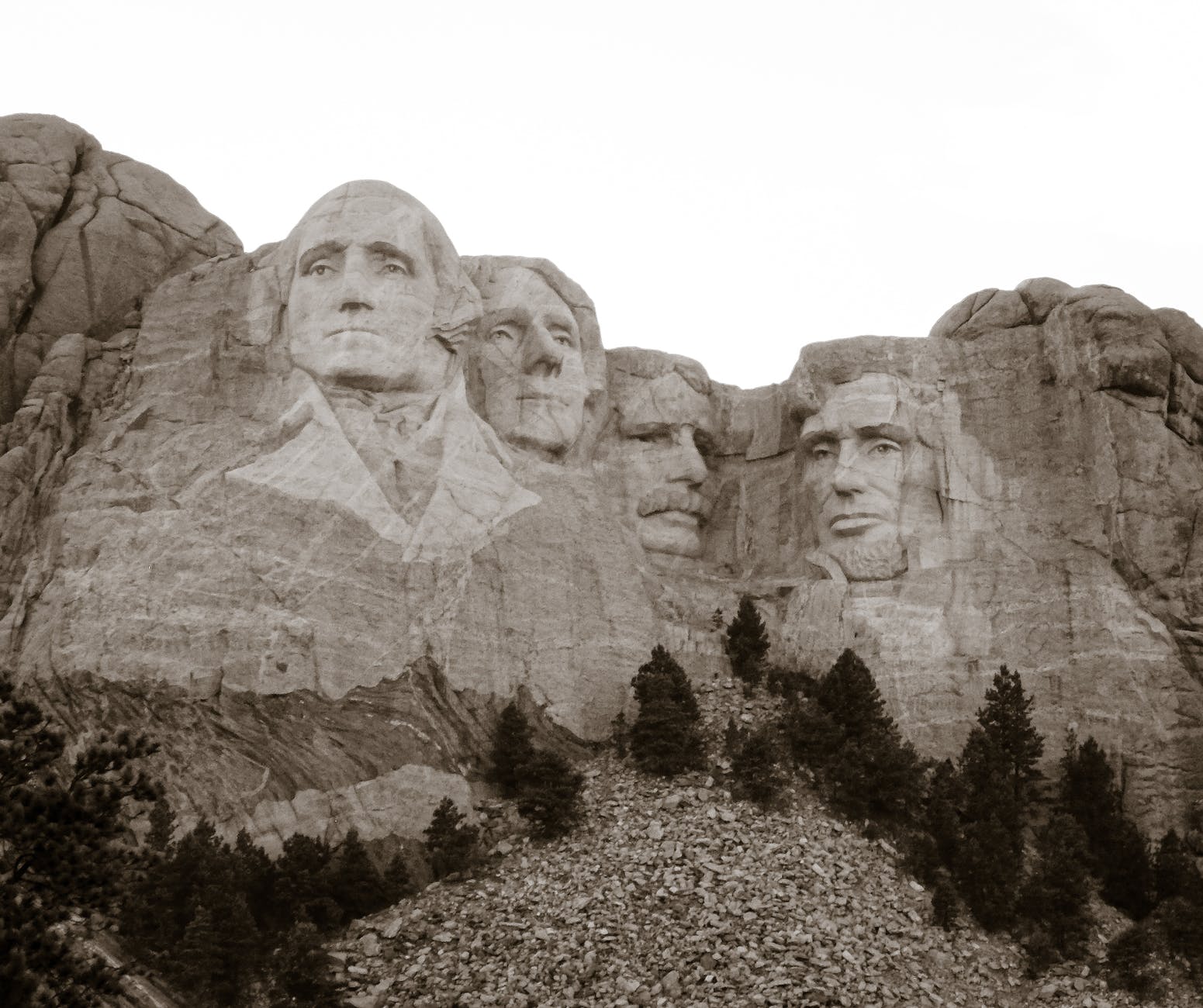

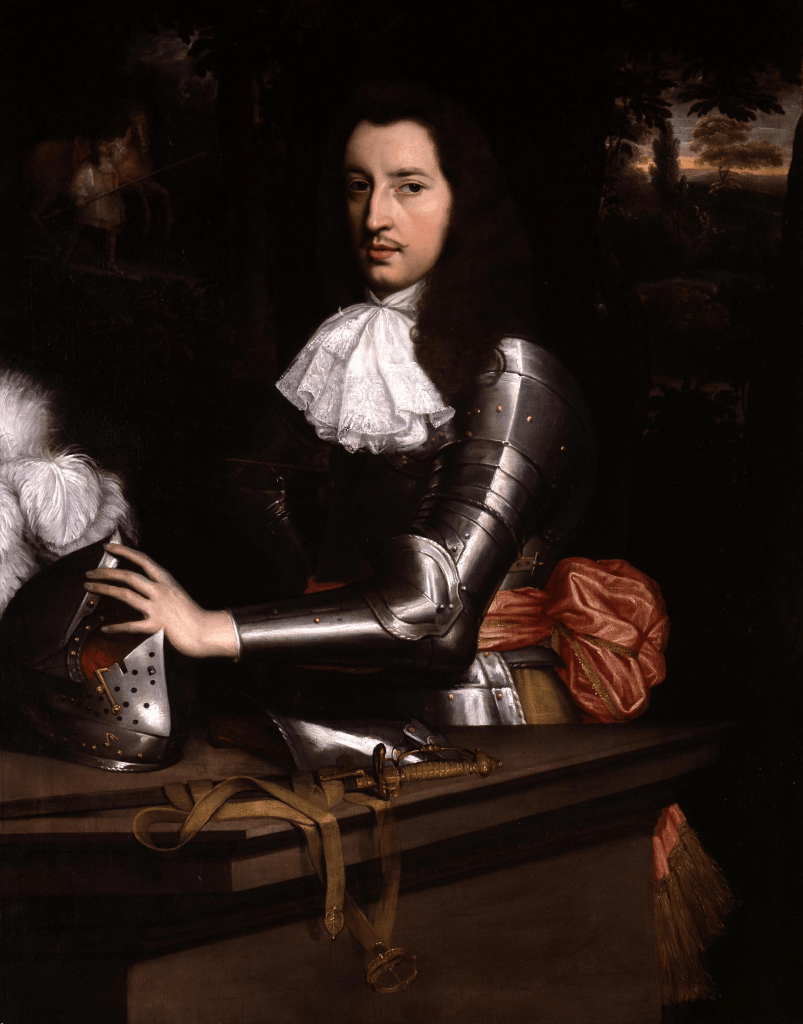

Inset picture of Henry, 6th Duke of Norfolk:

The Rule Against perpetuities was only later refined in the case Cadell v. Palmer (1833), 7 Bli. N.S. 202:

“Every attempted disposition of land or goods is void, unless, at the time when the instrument creating it takes effect, one can say, that it must take effect [if it take effect at all] within a life or lives then in being and 21 years after the termination of such life or lives, with the possible addition of the period of gestation.”

A better formulation was put by the American legal Scholar John Chipman Gray:

“No interest is good unless it must vest, if at all, not later than twenty-one years after some life in being at the creation of the interest.”

This area of law is legendary for its complexity, but the basic idea is that the rule allows enough time for unborn grandchildren to attain the age of majority before assets in trust are vested in them: A creates a trust with the intention of leaving assets to his daughter B’s children should she have any. If B gives birth and dies that same day, then the 21 years provides the time for the child C to reach age of majority and have the assets vested in them.

The rule has undergone a long series of alterations since its original inception, mainly through the Perpetuities and Accumulations Act 1964 and more recently the Perpetuities and Accumulations Act 2009, which set the perpetuity period at a flat 125 years.2

In America many states now no longer follow the Rule Against Perpetuities and allow perpetual trusts or dynasty trusts. The pattern started with then Governor of South Dakota William ‘Wild Bill’ Janklow.

Inset picture of ‘Wild Bill’:

Photo from The Guardian Newspaper. Janklow had initial success removing restrictions on credit card interest rates, thus persuading credit card companies to relocate their operations to South Dakota. His next operation was to write a law allowing the creation of perpetual trusts.3 Initially South Dakota emerged as a global tax haven. Other states soon followed in a race to the bottom and in recent time the count of States that allowed dynasty trusts stood at 21 in total.4 South Dakotan trust companies now hold hundreds of billions of dollars in assets.5 Questions were however soon asked about which parties benefited other than the financial and legal professionals who encouraged the creation of these trusts.

But on the other hand perhaps the 21 states legalising dynasty trusts have it right; that the ‘dead hand’ of trusts which reached too far in to the future was not enough of an affront to future commerce and dignity to merit their prohibition. Perhaps the ‘dead hand’ need not be so dead after all. Times may have changed.

However, returning to Lord Kames’ analysis:

‘[We] are not satisfied with the full enjoyment of the goods of fortune, unless it be also in our power to give them a perpetual existence, and to preserve them for ever to ourselves and our families.’

Is it not this thirst for the absolute that we feel so strongly. Absolute guarantee of our dynasty, and absolute power over what happens on the land we own. Land ownership comes with rights, but it increasingly comes with restrictions and responsibilities.

One right that comes with residential property, and traditionally with agricultural land, is the right of exclusion. There are some who choose to build the whole construct of ownership based on concepts of exclusion and use.6 It was one of the first instincts of European settlers under the Homestead Act of 1862 to exclude cowboys and their migrating herds of cattle from their land. This desire for exclusion was expressed as a desire for enclosure, and with the invention of barbed wire by John Warne Gates this became possible. Gates described his invention of barbed wire as “lighter than air, stronger than whiskey, cheaper than dust” and it transformed America within a matter of years from a land of herding cowboys to a nation of homesteads and agricultural partitions.

In America exclusion is advertised at its most extreme by the castle doctrine, which is followed by the majority of US states. Under the castle doctrine the threat of an intruder to life or limb on home property may be met with defence up to and including deadly force. The usual duty to retreat when threatened rather than ‘standing your ground’ is dispensed with – the concept is similar to that of justifiable homicide but the bar for what motivates a ‘defensive attack’ significantly lower.

Photo by Connor Steinert on Pexels.com A tragic example of the consequences is that of Yoshihiro Hattori, a Japanese exchange student visiting Baton Rouge, Louisiana in 1992. He and another student, Webb Haymaker set out to join a Halloween party but got the wrong house. The resident Rodney Paiers had an encounter with the two students in which he was armed with a handgun. He told the pair to ‘freeze’, but in the confusion and with limited knowledge of Englsih Hattori continued to approach Paiers, perhaps believing the situation to be a Halloween prank.It is possible Hattori’s camera was mistaken for a weapon. Paires shot Hattori, who died soon afterwards. Initially the Baton Rouge Police Department refused to charge Paires for any crime on the basis he was ‘within his rights in shooting the trespasser.’ The incident did eventually make its way to trial where Rodney Paires was acquitted of manslaughter, to the applause of the courtroom.

Photo by Kelly on Pexels.com There are numerous cases of gun deaths in this residential setting and they typically follow the same pattern: confrontation, misunderstanding or overreaction, firearm easily accessible, fatal shooting. They illustrate the level of protectiveness people have over their home.

This alertness to intrusion is also illustrated by the proportion of people who feel compelled to move to a different property following a break in or ‘home invasion.’ According to home insurer Policy Expert, 12% of burglary victims moved homes as a result of the intrusion. It’s as if the property becomes ‘soiled’ in the mind of the victim and they can’t square with remaining there.

The land which is our home clearly forms a deep part of our emotional makeup. The highly influential Swiss psychoanalyst Carl Gustav Jung believed that when a house appeared in a dream, the house was a metaphor for the psyche. He himself had a dream he associated with this finding:

“I was in a house I did not know, which had two storeys. It was “my house”. I found myself in the upper storey, where there was a kind of salon furnished with fine old pieces in Rococo style. On the walls hung a number of precious old paintings. I wondered that this should be my house and thought “not bad”. But then it occurred to me that I did not know what the lower floor looked like. Descending the stairs, I reached the ground floor. There everything was much older. I realised that this part of the house must date from about the fifteenth or sixteenth century. The furnishings were mediaeval, the floors were of red brick. Everywhere it was rather dark. I went from one room to another thinking “now I really must explore the whole house.” I came upon a heavy door and opened it. Beyond it, I discovered a stone stairway that led down into a cellar. Descending again, I found myself in a beautifully vaulted room which looked exceedingly ancient. Examining the walls, I discovered layers of brick among the ordinary stone blocks, and chips of brick in the mortar. As soon as I saw this, I knew that the walls dated from Roman times. My interest by now was intense. I looked more closely at the floor. It was of stone slabs and in one of these I discovered a ring. When I pulled it, the stone slab lifted and again I saw a stairway of narrow stone steps leading down to the depths. These, too, I descended and entered a low cave cut into rock. Thick dust lay on the floor and in the dust were scattered bones and broken pottery, like remains of a primitive culture. I discovered two human skulls, obviously very old, and half disintegrated. Then I awoke.”

Jung interpreted the house in the dream as representing his psyche, with the upper levels representing his normal consciousness, ranging down to the lower primitive levels which represent his instincts and collective unconscious; that is; the collection of knowledge and imagery shared by all through ancestral experience.

Photo by Binyamin Mellish on Pexels.com So a home forms a key part of our psyche and may be an expression of our self on the deepest level. How far this extends to wider (perhaps agricultural) lands remains unclear, but some things are for sure: humans have a strong desire to preserve and perpetuate their wealth, sometimes desiring that it benefit their descendants indefinitely. Added to this we have a strong instinct to exclude others from the spaces we have actual ownership of, and can easily find ourselves using lethal force to ‘stand our ground’ as we interpret a stranger is ‘in the wrong place;’ according to our deepest instincts about our territory.

All this together makes for a somewhat tyrannical evaluation of the human condition with relation to land ownership.

Statute:

Perpetuities and Accumulations Act 1964

Perpetuities and Accumulations Act 2009

Case Law:

The Duke of Norfolk’s Case

Cadell v. Palmer (1833), 7 Bli. N.S. 202:

References:

1. Law Articles. Rule against perpetuity and its exceptions: A sine qua non of property transfer. https://www.legalservicesindia.com/law/article/1030/8/Rule-against-perpetuity-and-its-exceptions-A-sine-qua-non-of-Property-transfer. Updated 2018.

2. Law Commission. Perpetuities and accumulations: Current project status. https://www.lawcom.gov.uk/project/perpetuities-and-accumulations/. Updated n.d.

3. Heller M, Salzman J. Mine: How the hidden rules of ownership control our

-

The Future of Compulsory Purchase

Not even holy ground escapes compulsory purchase, places of worship are acquired much like other land: see London Transport v Congregational Union [1979]. Expropriation in the UK comes under scrutiny as emotions run high with projects such as Crossrail, HS2 and two new nuclear power stations in the pipeline. But how can the UK’s compulsory purchase system change to make projects more efficient, while being more transparent and fair to those affected?

It helps to understand the origins of the principles behind statutory compulsory purchase. The story starts with the emergence of the individual as a person protected in some way against the State (or Crown). The first half of the Middle Ages was characterised by manorialism and feudalism.1 Feudalism is commonly understood, however the lesser known manorialism refers to community life centralised around the manor, with agricultural work provided to the local lord by the common man in exchange for his subsistence. These systems became disrupted, in part due to the emergence of a market economy, where produce and interests in land began to be bought and sold with money. Gradually over the last millennium, the individual has emerged, and the key juncture in the form of the Magna Carta of 1215 came as a direct challenge to unbridled feudalism, bestowing a certain class of individuals with rights upheld against the primacy of the English Crown. There were similarly inspired agreements on the Continent, starting with the Hungarian Golden Bull edict of 1222 or ‘Aranybulla.’ Folklore tells that European knights together out on crusade conspired in their demands for the emergence of fundamental rights across Europe. What is more certain is that the agreements were reached as a response to the decline of the manorial and feudal power structures. The most famous clause 39 of the Magna Carta reads2:

“No free man shall be seized, imprisoned, dispossessed, outlawed, exiled or ruined in any way, nor in any way proceeded against, except by the lawful judgement of his peers and the law of the land.”

Our focus is the issue of dispossession according to the law. In England compensation for dispossession was soon commonplace where the Crown lawfully fulfilled its responsibility for transport by road and river. 1539 brought the first statutory compulsory purchase,3 that is, one by an act of Parliament under royal prerogative, rather than by the Crown itself. Land was taken for the cutting of a canal giving by-water access to Exeter, and compensation was paid at 20 years rent.

Photo by Anastasiya Lobanovskaya on Pexels.com This system of passing specific ‘private’ or ‘local’ acts to authorise compulsory purchase continued act-by-act until the Lands Clauses Consolidation Act 1845, which codified the conditions for compulsory purchase; this could then conveniently be incorporated into future acts by reference. The main provisions from the 1845 Act can today be found in the Compulsory Purchase Act 1965 and the regulations governing compulsory purchase in England are to be found in4:

- The Acquisition of Land Act 1981 in the form of the most common Compulsory Purchase Order (CPO).

- The Transport and Works Act 1991, tailored towards railways and trams,5 and more recently:

- The Planning Act 2008 in the form of the Development Consent Order (DCO), for large, Nationally Significant Infrastructure Projects (NSIPs).6

Photo by Recal Media on Pexels.com Today the rights found in clause 39 of Magna Carta, generally, can be found in the European Convention on Human Rights, to which the UK is party, and which entered into force in 1953.7

Reform in the UK

‘It has been widely acknowledged for over two decades, however, that the law of compulsory purchase in England and Wales is fragmented, hard to access and in need of modernisation.

The Law Commission 20048

There have already been attempts to reform the compulsory purchase system in the UK. Successful changes were made to the tribunals system under the Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007, the old Lands Tribunal was replaced by the Upper Tribunal in 2009,9 with the First-tier Tribunal (Property Chamber) now active at the time of writing.10 The Law Commission have been developing ideas around a Compulsory Purchase Code, – not to be confused with a civil law code.11,12 The recommendations of the Law Commission have not been implemented.8,13 For the sake of creating a novel publication, we will refrain from recycling suggestions here that have been made elsewhere.

Injustice

In a perfectly just world, compensation would be paid for any kind of genuine disruption due to a scheme, but law cannot permit this, if it did the floodgates would surely open… ‘to a liability in an indeterminate amount for an indeterminate time to an indeterminate class’: Cardazo C.J. in Ultramares Corp. v Touche (1932) (US).

In an imperfect world there are injustices. For example, in a rural setting where land and farmer become strongly linked, schemes sever farms; permanently in the cases of road and rail. Often along a route all those affected take part in an over-competitive and inflated local market as they seek new land or premises to marry what they have left; this is a market which the compensation they have been given does not necessarily reflect. Issues of land concentration, which makes suitable sized plots of new land difficult to find, add to the problem.14 Those who move to new and more costly premises, perhaps with limited alternatives, are all too often told that they have ‘received additional value;’15 that is that the new property offers certain advantages the old property did not; they are therefore not to be compensated based on the new cost despite having little choice in the matter.

Agricultural, commercial, whatever the setting; those whose land is acquired are not entitled to direct compensation for all profits lost as a result of the acquisition. The traditional argument goes that future profits in a ‘no-scheme world’ are automatically rolled into the market value of the land already compensated for and therefore merit no further compensation.16 ‘Goodwill’; that is, the profits developed by the occupier above and beyond the profits derived from the land itself, are however admittedly compensatable.17 However it seems that the degree to which the standard profits are rolled into a market value could be too easily overestimated, and the true value of the ‘goodwill’ element too easily underestimated. The classic case cited, despite the flawed nature of the plaintiff’s claims, is ‘the fish and chip shop case’: Mohammed & Ors v Newcastle City Council [2016] where an (unsuccessful) claim based on loss of profits was attempted.

One option stands out as a cure to these two key injustices; perhaps the re-introduction of the ‘solatium’ that existed universally in the UK before 1919; that is; the paying of a premium upon the compulsory acquisition of all interests in land; would compensate more fairly the reality of compulsory purchase for those who live under the cloud of compulsory acquisition.18

Moreover, the giving of offers ‘subject to contract’ by acquiring authorities also expose those affected by expropriation to unduly harsh circumstances. Where the acquiring authority makes an offer following a notice to treat, they can mark the offer ‘subject to contract.’ A typical claimant may then depend upon this offer, or even secure bridging finance, to acquire a new property. But the offer is not set in stone, and the acquiring authority can turn around and slash the price, leaving the claimant in an ‘impossible’ position as they have already arranged to purchase another property.19

What happens when the acquiring authority enters or takes possession of land without the appropriate powers, surely such an affront to fundamental rights would be taken seriously?

If the acquiring authority should enter unlawfully there is a fine of £10 payable.20 There is the obligation to compensate any damage done in entering unlawfully, but nonetheless the almost complete lack of compensation for an act against the fundamental rights of the landowner seems quite unwarranted. The reason for entering the land (unlawfully) would likely be in connection with the building of infrastructure or significant development, usually with millions of pounds of investment involved, and we know the sums paid by willing developers and utility companies for land interest questionnaires and non-intrusive licences are in the hundreds of pounds, so to pay pittance for a breach that is significant in principle seems dissatisfactory. There will be professional fees for the landowner to pay in fighting such an ingress. Even where a claimant seeks redress at common law for damages for trespass such as in National Provident Institution v Avon County Council [1992], the damages paid can be minimal. Here demolition was undertaken by the acquiring authority on the land of the plaintiff, on whose land no compulsory purchase powers existed. The damages paid to the claimant were only £200 in today’s money.21 Crucially; court legal costs were payable by the plaintiff as it was deemed they had effectively lost the case against the acquiring authority. So there is no right to significant damages based upon the fact that works have been carried out on land with no confirmed CPO, and claimants should be held back for fear of the costs of litigation. All this together puts the developer in an unusual position of power, with scope for negligence without consequence. There is a natural inclination to support the underdog; but the metaphorical boot is on the authority’s foot.

These last two injustices could be legislated against effectively; firstly, by making offers of the acquiring authority final from their side; that is, each time the landowner accepts an offer of the acquiring authority, the acquiring authority should not be at liberty to withdraw or change the offer. The issue of entry without consent could be tackled with a fine based upon the yearly turnover of the acquiring authority or the total value of the scheme, this hopefully proportionally ensuring increased respect and caution on the behalf of the acquiring authority.

Comparison with a Civil Law Jurisdiction

It is interesting to consider a civil law jurisdiction, where judgements are (commonly assumed) to follow a civil code, rather than a combination of statute and case law. Judges in civil law jurisdictions do in fact draw inspiration from case law depending upon the jurisdiction; there is a good talk by Holger Spamann of Harvard Law School on this topic.22

At the turn of the century Vienna was the capital of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, with the Civil Service, and its civil codes as the jewel of its crown. Today Austria is a federation of nine states of which Vienna is the largest by population. Each state has their own Bauordnung (BO) or Building Law.23 The core principles for compulsory purchase and compensation in Vienna are set out in the Bauordnung für Wien in sections 38-46, with sections 57-59 reserved explicitly for the issue of compensation.23 There have recently been infrastructure projects with significant expropriation consequences such as the U2/U5 U-Bahn (Underground Mass-Transit) extension, which will conclude in 2028.24-26 Notwithstanding significant projects in a large city the application form for compulsory purchase under the Bauordnung für Wien is only one page long.27

Other states in Austria have similarly compact civil codes which have provided for the building of vast projects like the Brenner Autobahn (Brenner Pass Motorway), in Kärnten (Corinthia), this motorway forming a backbone of European North-South transit. Indeed the Kärntner Bauordnung or Corinthia Building Code has a total of only around 50 sections and articles (50 paragraphs).28 Infrastructure expansion continues: the question as to why Austrians dwelling in sleepy valleys should have their homes compulsorily purchased to make way for freight between Germany and Italy is frequently a hot topic on ORF radio.29

There are also federal laws (Bundesgestze) that deal with compulsory purchase for particular types of infrastructure and development. These include:

- Eisenbahn-Enteignungsentschädigungsgesetz or Railway Expropriation Compensation Law, the EisbEG.

- Bundesstraßengesetz or Federal Roads Law, the BStG 1971.

- Bodenbeschaffungsgesetz of 1974 or Land Procurement Law. See the recent circumstances in Innsbruck.30,31

These federal laws carry out a similar function to the ‘enabling acts’ in UK compulsory purchase law.

All of the same main principles of expropriation run through the UK and Austrian legislation. However, looking more closely at the Austrian legislation; it has a different style to the UK legislation. The UK legislation reads much like ‘computer-code,’ with single lines of text linked logically in a kind of ‘if’, ‘only-if’ fashion. In contrast, an Austrian section consistently consists of one paragraph of medium length, altogether describing, framing, in the most reasonable way the issue it seeks to address and its context. Rather, the UK legislation is written in a rather paranoid fashion, perhaps constantly seeking to prevent circumvention of parliament’s intent; but surely a member of the judiciary would spot an advocate who seeks to interpret vexatiously.

Perhaps we could incorporate more of the Austrian style into our legislation, particularly when starting from scratch, as would be the case if writing a compulsory purchase code. The legislation should be less prescriptive and more descriptive. The Austrian approach requires that judges are allowed to gather just interpretation from legislation, rather than apply it letter for letter, judges must therefore be permitted significant freedoms. It is interesting that the old Lands Tribunal in the UK was not bound by precedents set by itself, although it was bound by decisions of the Court of Appeal.32

Accessibility and Efficiency

Statute and case law have different characteristics, statute is a precise prescription, the interpretation of which is limited and constricted, but it can be made fairly rapidly by the two houses of Parliament. Case law provides inspiration for just interpretation, but for it to be made the correct case must present itself, and new precedents are restricted in that they can only follow as adaptation and evolution of existing case law. Statute and case law must be used in the correct circumstances respectively to achieve the most efficient law.

The principles of compensation law in the UK are scattered amongst ten or so statutes (excluding enabling acts, and there is a clear benefit to having a different act for each kind of infrastructure or development). As compensation law has grown it has inevitably become more complex, however this increase in complexity could likely be reduced significantly through the considerable task of centralising all of the current principles into one, two, or possibly three comprehensive statutes.

Codification: some areas of law are unjust or outmoded or have become overly sophisticated, and this is a clear impetus to codify. But codification and re-codification can create serious problems; take for example the most recent Electronic Communications Code brought in by the Digital Economy Act 2017. There have been significant teething problems with this new code, with polarisation of claims and significant litigation taking place, partly because of an over-literal interpretation of the code regarding rent: in CTIL v Compton Beauchamp [2022], CTIL, otherwise Cornerstone Telecommunications, tried to interpret the new Code to produce a rent of £26 per annum for a mast site. This is clearly dissatisfactory as no willing landowner would accept this figure.33

Finally; legislation becoming outmoded is inevitable, but excessive sophistication is less forgivable: s. 14(3) of the Land Compensation Act 1961 regarding compensation and planning permission reads:

‘Nothing in those provisions shall be construed as requiring it to be assumed that planning permission would necessarily be refused for any development which is not development for which, in accordance with those provisions, the granting of planning permission is to be assumed…’

This kind of composition wastes time and is apt to produce unfortunate misinterpretation; it shouldn’t be difficult to avoid.

Three Parties to a Compulsory Purchase

Lord Denning in Prest v Secretary of State for Wales [1982]:

‘I regard it as a principle of our constitutional law that no citizen is to be deprived of his land by any public authority against his will, unless it is expressly authorised by Parliament and the public interest decisively so demands…’

Building upon the theme of the public interest laid down by the ECHR and Denning’s comment above in Prest regarding balance of the public interest and compensation: it is an interpretation that compulsory purchase is not just an exchange between the acquiring authority and they who have an interest in the relevant land. It is rather a tripartite interaction between landowner, the acquiring authority, and crucially the public, for the acquiring of the land hinges upon the transaction being in the public interest.34 In the words of Lord Greene MR: ‘There is a third party who is not present, viz., the public’ in B Johnson & Co (Builders) Ltd v Minister of Health [1947]. Following privatisation of utilities, road, rail and airports, we have to ask who expropriations under privately owned acquiring authorities really serve; do they sacrifice the land of occupants in the interest of the public, or in the interest of FTSE 100 shareholders?

And so why not, with projects ranging from local developments up to NSIPs, give the public a say on whether projects requiring expedient compulsory purchase of extensive private property should go ahead. Switzerland has a pervasive system of referenda at both the federal and cantonal (local state) level with multiple federal level referenda per year. There have been Swiss referenda on infrastructure projects, including hydro-power schemes and dams in particular.35 Electronic voting is highly enabling and as our democracy evolves, referenda could be an effective way to create mandates for infrastructure projects at a local level and at a national one. It is unclear whether projects put to referendum would be stymied at the local level by ‘NIMBYism’ or whether large infrastructure projects would be vindicated as the many the projects serve vote against the minority who are negatively impacted.

The Information Age

Photo by Pixabay on Pexels.com Digitalisation provides significant scope for more efficient delivery of nationally important projects which require compulsory purchase. The success of the digital tools employed by the Rural Payments Agency in delivering subsidies under the Basic Payment Scheme (BPS) shows how digital mapping and land parcel referencing can be highly effective for agricultural holdings. Utilities agents have already started to develop their own software which they use to negotiate and interact with clients and those affected by compulsory purchase for infrastructure projects such as pipelines and grid connections.36 Yet it remains to be seen if software can be developed that deals with land interests in an urban setting, such as, for example, central London. The question is whether the software can be developed in a way that makes information about interests in land manageable for the user.37 Indeed in a city, as ownerships and burdens are stacked on top of each other and intersect so frequently the entry of the data and its interpretation become less intelligible.

A significant barrier to compulsory purchase being carried out efficiently and fairly is the process of deciding where infrastructure links or developments will go. Although surveyors do form Land Interest Groups to represent their clients’ interests more effectively, agents representing the acquiring authority will typically meet with clients and those who act for them one-by-one. This means that information about the preferences of the acquired is submitted in a piecemeal fashion and often not made coherent with the preferences of neighbours. Perhaps it is time to formalise a digital system where those with interests of land can express which assets mean the most to them, so that different parties’ priorities can be set off against each other. Software development is now advanced enough that a system could be created where landowners are given, for example, fifty points for every £100,000 of property they own. Landowners would then distribute these points to land interests they own on a digital map that includes land parcels and real-estate. The final route of the infrastructure link is then digitally optimised to avoid areas of high priority/intensity/interest, with a numerically defined path that provides minimal disruption. Could this be the future of route determination for large infrastructure links and pipelines?

Initially we came to the conclusion that the current system is skewed in favour of acquiring authorities, with little room for sentiment on the part of those acquired. There are indeed a few injustices to be found, a realistic remedy to compensate being the re-introduction of a bonus payment or ‘solatium’ over and above the market value of land acquired, as existed pre 1919. To make the relevant law more easily understandable and efficient, legislators, drafters and judges need to use statute and case law in their proper places respectively. Indeed Austrian expropriation law demonstrates that it is possible to legislate even for large infrastructure projects using a compact code. An overhaul in the form of a single compulsory purchase code may be necessary. Digitalisation provides possibilities for mapping and prioritisation of interests parties have in land. Furthermore, digital direct democracy in connection with local and nationally significant infrastructure projects provides significant opportunities for increased efficiency, transparency and justice.

UK Statute

Lands Clauses Consolidation Act 1845

Land Compensation Act 1961

Acquisition of Land Act 1981

Transport and Works Act 1991

Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007

The Planning Act 2008

Digital Economy Act 2017

Austrian Legislation: State

Bauordnung für Wien StF.: LGBl. Nr. 11/1930

Kärntner Bauordnung 1996 StF: LGBl Nr 62/1996 (WV)

Austrian Legislation: Federal

Eisenbahn-Enteignungsentschädigungsgesetz: EisbEG: StF: BGBl. Nr. 71/1954 (WV)

Bundesstraßengesetz StF: BGBl. Nr. 286/1971

Bodenbeschaffungsgesetz StF: BGBl. Nr. 288/1974

Case Law: UK

Ashbridge Investments Ltd v Minister for Housing and Local Government: [1965] 1 WLR 1320, [1965] 3 All ER 371

Associated Provincial Picture Houses Limited v Wednesbury Corporation [1948] 1 K.B. 223

Birmingham City Corpn v West Midlands Baptist Trust [1969] UKHL, [1970] AC 874, [1969] 3 All ER 172

Attorney-General v De Keyser’s Royal Hotel [1920] UKHL 1, [1920] AC 508

B Johnson & Co (Builders) Ltd v Minister of Health [1947] 2 All ER 395

Cornerstone Telecommunications Infrastructure Ltd (Appellant) v Compton Beauchamp Estates [2022] UKSC 18

London Transport Executive v Congregational Union of England and Wales Inc (1978) 37 P & CR 155, [1978] RVR 233, 249 Estates Gazette 1173

Mohammed & Ors v Newcastle City Council [2016] UKUT 415 (LC)

National Provident Institution v Avon County Council [1992] EGCS 56

Prest v Secretary of State for Wales (1982) 81 LGR 193, 198

Roberts v Coventry Corporation [1947] 1 All E.R. 308

Street v Mountford [1985] UKHL 4, AC 809, 2 WLR 877

Case Law: US

Ultramares Corp. v Touche 174 N.E. 441 (1932) (US)

References

1. Maitland-Biddulph R. Feudalism, manorialism and succession. https://landed.blog/2022/07/16/land-ownership-part-i-feudalism-manorialism-and-succession/. Updated 2022.

2. UK Parliament. The contents of magna carta. https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/evolutionofparliament/originsofparliament/birthofparliament/overview/magnacarta/magnacartaclauses/. Updated 2023.

3. The Parliamentary Archives, Gadd S. 1539: The origin of statutory compulsory purchase of land for transport development. https://archives.blog.parliament.uk/2018/09/22/1539-the-origin-of-statutory-compulsory-purchase-of-land-for-transport-development/. Updated 2018.

4. Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities. Guidance: Compulsory purchase and compensation: Guide 1- procedure. https://www.gov.uk/guidance/compulsory-purchase-and-compensation-guide-1-procedure. Updated 2021.

5. Department for Transport. Guidance: Transport and works act orders: A brief guide. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/transport-and-works-act-orders-a-brief-guide-2006/transport-and-works-act-orders-a-brief-guide. Updated 2013.

6. The Planning Inspectorate. National infrastructure planning. https://infrastructure.planninginspectorate.gov.uk/. Updated 2012.

7. Council of Europe. European convention on human rights. . 2010.

8. The Law Commission. Compulsory purchase: Current project status. . Updated 2004.

9. Denyer-Green B. Compulsory purchase and compensation. 11th ed. Routledge; 2019:120, 121.

10. HM Courts & Tribunals Service. First-tier tribunal (property chamber). https://www.gov.uk/courts-tribunals/first-tier-tribunal-property-chamber. Updated 2023.

11. The Law Commission. Towards a compulsory

purchase code:

(1) compensation. https://www.lawcom.gov.uk/app/uploads/2015/03/cp165_Towards_a_Compulsory_Purchase_Code_Consultation1.pdf. Updated 2003.12. The Law Commission. Towards a compulsory

purchase code:

(2) procedure. https://s3-eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/lawcom-prod-storage-11jsxou24uy7q/uploads/2015/03/lc291_Towards_a_Compulsory_Purchase_Code2.pdf. Updated 2004.13. The Law Commission. Towards a compulsory purchase code: Current project status. https://www.lawcom.gov.uk/project/towards-a-compulsory-purchase-code/. Updated 2004.

14. Russel K, Central Association of Agricultural Valuers. #8 – good practice in statutory compensation claims. https://www.caav.org.uk/resources/podcasts/8-good-practice-in-statutory-compensation-claims. Updated 2020.

15. Denyer-Green B. Compulsory purchase and compensation. 11th Edition ed. Routledge; 2019:259.

16. Denyer-Green B. Compulsory purchase and compensation. 11th Edition ed. Routledge; 2019:264.

17. Denyer-Green B. Compulsory purchase and compensation. 11th Edition ed. ; 2019:262.

18. Denyer-Green B. Compulsory purchase and compensation. 11th ed. Routledge; 2019:168.

19. Denyer-Green B. Compulsory purchase and compensation . 11th ed. ; 2019:87.

20. Denyer-Green B. Compulsory purchase and compensation. ; 2019:115, 116.

21. Bank of England. Inflation calculator. . 2023. https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/monetary-policy/inflation/inflation-calculator.

22. Spamann H. Holger spamann examines the myths and reality of common and civil law. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uHrtq-hCiwo. Updated 2022.

23. Rechtsinformationsystem des Bundes, Bundesministerium für Finanzen. Bauordnung für wien. https://www.ris.bka.gv.at/GeltendeFassung.wxe?Abfrage=LrW&Gesetzesnummer=20000006. Updated 2023.

24. Stadt Wien. Mit der U5 vom karlsplatz bis hernals. https://www.wien.gv.at/stadtentwicklung/projekte/verkehrsplanung/u-bahn/u2u5/linie-u5.html. Updated 2023.26. Pflugl J. Wiener linien compensated around 2,200 owners for the new subway. https://www.derstandard.at/story/2000129445382/wiener-linien-entschaedigten-wegen-neuer-u-bahn-rund-2200-eigentuemer. Updated 2021.24. Stadt Wien. Mit der U5 vom karlsplatz bis hernals. https://www.wien.gv.at/stadtentwicklung/projekte/verkehrsplanung/u-bahn/u2u5/linie-u5.html. Updated 2023.

25. Stadt Wien. U-bahn-ausbau U2 und U5. https://www.wien.gv.at/stadtentwicklung/projekte/verkehrsplanung/u-bahn/u2u5/. Updated 2023.

26. Pflugl J. Wiener linien compensated around 2,200 owners for the new subway. https://www.derstandard.at/story/2000129445382/wiener-linien-entschaedigten-wegen-neuer-u-bahn-rund-2200-eigentuemer. Updated 2021.

27. Magistratsabteilung 64 für Wien. Ansuchen um grundenteignung. https://www.wien.gv.at/ma64/ahs-info/pdf/enteignung-baurecht.pdf. Updated 2023.

28. Rechtsinformationsystem des Bundes, Bundesministerium für Finanzen. Kärntner bauordnung. https://www.ris.bka.gv.at/GeltendeFassung.wxe?Abfrage=LrK&Gesetzesnummer=10000201. Updated 2023.

29. Österreichischer Rundfunk. Österreichischer rundfunk. https://orf.at/. Updated 2023.

30. Balgaranov D. Innsbruck declares a ‘Housing emergency’. https://www.themayor.eu/en/a/view/innsbruck-declares-a-housing-emergency-10730. Updated 2022.

31. Putschögl M. Enteignungen: Das innsbrucker experiment. https://www.derstandard.at/story/2000138276599/enteignungen-das-innsbrucker-experiment. Updated 2022.

32. Denyer-Green B. Compulsory purchase and compensation. 11th Edition ed. Routledge; 2019:122.

33. Moody J. CAAV podcast #3 – the electronic communications code – still in stasis? . Updated 2020.

34. Denyer-Green B. Compulsory purchase and compensation. Routledge; 2019:41.

35. Schuler M, Dessemontet P. The swiss vote on limiting second homes. https://journals.openedition.org/rga/1872?gathStatIcon=true. Updated 2013.

36. Dalcour Maclaren. Experience with dalcour maclaren. . 2023.

37. LandTech Group Pty Ltd. LandTech. https://pages.land.tech/land-for-sale-content?keyword=land%20insite&utm_campaign=GoogleAds&utm_source=ppc&utm_medium=ppc&utm_term=land%20insite&hsa_kw=land%20insite&hsa_net=adwords&hsa_grp=144891663306&hsa_cam=19584313178&hsa_acc=8666086076&hsa_tgt=kwd-1944688311988&hsa_ver=3&hsa_ad=642783927106&hsa_mt=b&hsa_src=g&gclid=CjwKCAiAmJGgBhAZEiwA1JZolippLtbh_23HsgxJlsok2vXIrMUYSj0WWI5JZIbgQ__fSf1M_tsDnBoCBRcQAvD_BwE. Updated 2023.

-

Lead Shot – Guilty or Benign

Introduction

There are currently plans in the making to ban the use of lead shot in the UK1, 2. Indeed a de-facto ban may occur as meat suppliers refuse to take game that have been shot with lead ammunition. There are claims that lead shot kills hundreds of thousands of wildfowl annually. While these claims about danger to wildlife have been described as inflated, lead is an extremely damaging substance to human health when in sufficient quantities, with the potential to cause neurological damage, and even defects in DNA3. Indeed lead’s effects, in particular on the mind, were observed by the Greek Nikander of Colophon in the 2nd century BC, when white lead was used to sweeten wine. Over the last half-century sources of lead in the first world have been all but removed from gasoline, paint and water piping.

Abstract/Conclusion

The following mathematical work is quite involved, we therefore advise the reader who does not have the time or want to expend the effort to understand the following calculations to simply read the following abstract or conclusion for a potted outline of our findings:

The conclusion is a fairly balanced one. On the one hand, game or clay pigeon shooting has the potential to distribute very significant quantities of lead (sometimes >1 tonne/ha). Additionally, according to an exponential model, this lead saturates the environment at a very significant rate, reaching an equilibrium/saturation in under one year when the relevant land has been shot upon periodically going back 20 years or more. The environment does clearly become toxified.

How to break down the issue of lead exposure for adults engaged in game or clay shooting in the field is difficult and complex. There is exposure from handling weapons and ammunition, particulate in the air, and exposure to the environment itself.

The exponential model from a linear ordinary differential equation indicates that due to the low mass of birds, and the tendency for shot to get stuck in the gizzard, it is quite likely that a bird ingesting some pellets would experience lead poisoning. These conclusions were obviously also reached by the US Fish and Wildlife Service4 when they started designating steel-shot-only hunting zones for waterfowl as early as 19765. Perhaps we should look to the USA.

On the final issue of harm arising from human lead ingestion the conclusion is that due to the absence of a gizzard, and the relatively swift digestion and elimination that occurs in a human, it is very unlikely an adult would suffer lead poisoning from the ingestion of a reasonable number of lead pellets. Small children (with their small size and volume) who ingest slightly larger quantities of lead and may well experience toxicity however, particularly if the lead bodies become stuck in the digestive tract.

The Setting

The interest in the transfer of lead in lead pipes provides us with a linear ordinary differential equation for the diffusion of lead from water pipes6. We will attempt to adapt this model to lead shot in a variety of environments. We will tackle three problems.

- Does regular use of lead shot on an area used to shoot driven game cause the ground to become toxic by scientific standards?

- If a bird ingests a number of lead shotgun pellets could its blood lead concentration reach toxic levels could it suffer harm or die?

- If a human is to ingest a number of pellets, possibly on a regular basis, is it conceivable that the individual would suffer from some degree of lead poisoning?

The Differential Equation

Transfer of lead from a solid pipe in to stationary water within the pipe can be modelled by the ordinary linear differential equation7:

V dc/dt = MA (1 – c/E) (1)

Where V is the volume of water in the pipe in m3, c is the lead concentration of this water in micrograms/litre. A is the internal area of the pipe in m3. E is the equilibrium concentration, beyond which lead ceases to be transferred from the pipe into the liquid. M is the initial mass transfer rate in micrograms per m2 per second.

Many thanks to Vita Stembrera for providing the more intuitive form of this relationship.

The equation (1) does make some sense; the rate of change of concentration over the whole volume V is proportional to the area of the pipe and the rate of mass transfer, and decreases as the concentration approaches the equilibrium concentration or point of saturation.

This is known as an exponential model. And indeed when it is solved it gives us the exponential equation6:

c= E – (E – c₀) . exp( -AMT/VE ) (2)

For lead, from the work by Van der Leer et. al.6 we have that for a scenario with moderate plumbosolvency:

M = 0.10 micrograms/m2/sec

E = 150 micrograms/litre

Part 1: Lead shot falling on one Hectare

We will adapt the scenario with a pipe to an instance where we have one hectare of land, and we consider the top 5 cm of soil. We will liken the soil to water in its properties – in the UK there is significant moisture in the topsoil in almost all seasons.

So we have a volume:

100m*100m*0.05m = 500m3 = 500,000 litres

From wikipedia a #6 12-bore 28g (1 oz) cartridge contains 270 pellets. The average diameter for this standard pellet is 2.59mm. Therefore the surface area of a pellet using the formula for the surface of a sphere is 2.11 e-5 m2 in scientific notation.

The weights of pellets in grammes provided by wikipedia are not satisfactory. Clearly a #6 pellet cannot weigh 1.62g as this would mean a 28g load would only comprise around 17 pellets rather than the required 270. We therefore calculate the weight of a single pellet using the density of lead p = 0.0113 . A #6 pellet of diameter 2.59mm has a radius of 1.295mm and therefore a volume of 9.09mm3. The resulting mass is 0.103g per pellet, and indeed, if we multiply 0.103g * 270 = 27.7g, vaguely in line with 28g load we started our calculations with. So the mass of a single pellet is 0.103g.

On a typical pheasant drive it is reasonable to assume 8 guns take a total of twenty shots each, bearing in mind how common a miss with the second barrel is. Therefore the total number of shots that occur during the drive is 8 * 20 = 160 shots. The total number of pellets from one drive is therefore 160 * 270 = 43,200 pellets, weighing a total of 4.48 kg.

Assuming the pheasant drive has been shot ten times per year for twenty years the total number of pellets in the topsoil is 43,200 *10 * 20 = 8.64 million, with a total weight of 896kg. The total surface area of these pellets is the area per pellet multiplied by the number of pellets: 8.64 e6 * 2.12 e-5 = 183m2.

Going back to our differential equation, it is important to remember the result will be in micrograms of lead.

c= E – (E – c₀) . exp( AMT/VE )

We have from Van der Leer et. al.6 E = 150, M = 0.10, c₀ = 0, A = 183, V =500,000 .

Using the free online graphing tool Desmos we obtain the following plot:

What this tells us is that the equilibrium concentration comes near to being reached within around 200 days. Lead therefore diffuses and saturates the environment relatively rapidly.

Is lead at the equilibrium concentration dangerous?

Over the years the standards for lead concentration in drinking water has been gradually decreased. Starting at a maximum of 50 micrograms/l they were then reduced to 25 micrograms/litre. In 2013 the limit was reduced to 10 micrograms/l8. In fact, there are various substances added to drinking water in order to minimise lead concentrations9.

But our above model dealt not with drinking water but instead the environment in general, and it is notoriously difficult to model how a human will interact with the natural environment. In addition there is contact with lead through the handling of lead shotgun shells, and possibly much more significantly, through the inhalation of particulate during shooting itself. All these questions are impossible to answer, so we will move on to questions two and three which investigate whether ingestion of lead shot presents a health hazard to living creatures.

Lead Poisoning in Birds

The proposed plumbosolvency of E = 150 micrograms/litre that was used by Van der Leer et. al.6 does not reflect the digestive action of a human or animal. Nonetheless we will apply our exponential model to the problem of ingesting lead shot, modelling an organism as a body of water that absorbs lead from the metal pellets.

Let us assume that five pellets are ingested. We start with a duck; a fairly typical kind of wildfowl. Assume that a duck weighs 1kg. Then as the duck is composed mainly of water it has a volume of 1 litre. Model the duck as a volume of water with a total of five pellets providing a mass transfer of lead.

Again we use the solution to the diffusion equation:

c= E – (E – c₀) . exp( AMT/VE )

And with moderate plumbosolvency E = 150, c₀=0, V=1, M=0.1 .

The area of five pellets is 5 * 2.11 e-5 = 1.06 e-4 m2.

We get the following plot:

It takes longer (400-600 days) to achieve a steady state than in the previous graph showing diffusion over a hectare. However, the plumbosolvency level of 150 micrograms/litre is significantly over what is considered to be injurious to human health. Indeed the model reaches the 50 micrograms/litre level within only fifty or so days. It is therefore easy to imagine that shot stuck in the gizzard of a bird would cause significant poisoning and kill the bird well within its lifetime, and our model does not even account for any extra lead dispersal within the organism caused by the digestive process and chemicals.

Question 3: Lead Shot Digested by a Human

Assume that a person ingests five lead pellets and assume a human has a weight of 100kg and therefore, being mostly of water, a volume of 100 litres. The only variable we need to change from the above model for a bird is therefore volume. We get the following result:

But a human doesn’t have a crop or a gizzard. We do admittedly have an appendix but when something becomes stuck in the appendix this is considered an unlucky occurrence, not to be expected. From our graph lead levels do not reach significance for hundreds of days, based on this model, and with the human digestive system fully processing intake within a typical 24 hour time frame, it seems inconceivable that a human would suffer lead poisoning from ingestion of a reasonable number of lead pellets. However, there is the issue of the action of the digestive system to take in to account. Lead does react (albeit slowly) with hydrochloric and sulphuric acid, which are found in the human stomach. Nonetheless, checking pubmed.gov for case reports of adult lead poisoning from pellets or rounds returns no results.